PUKEREIJAT – BECOMING A SHAMAN

The training of a novice begins generally after marriage and is under the supervision of a ‘master’ from another uma, the paumat, usually an uncle, but never the novice’s father. Usually a few novices are trained together, by a few different paumat. For his commitment and dedication the paumat is generously rewarded with pigs and various other gifts and the growing bond between the paumet and the eventually new shaman also bring families of different umas closer together.

During the course of the novice’s training to become a shaman five major ceremonies take place, spread out over a couple of months. During these ceremonies non-relevant work is taboo for the entire community and preparations such as making of sufficient sago flour, collecting plenty of fire wood and bamboo for cooking is done all well in advance.

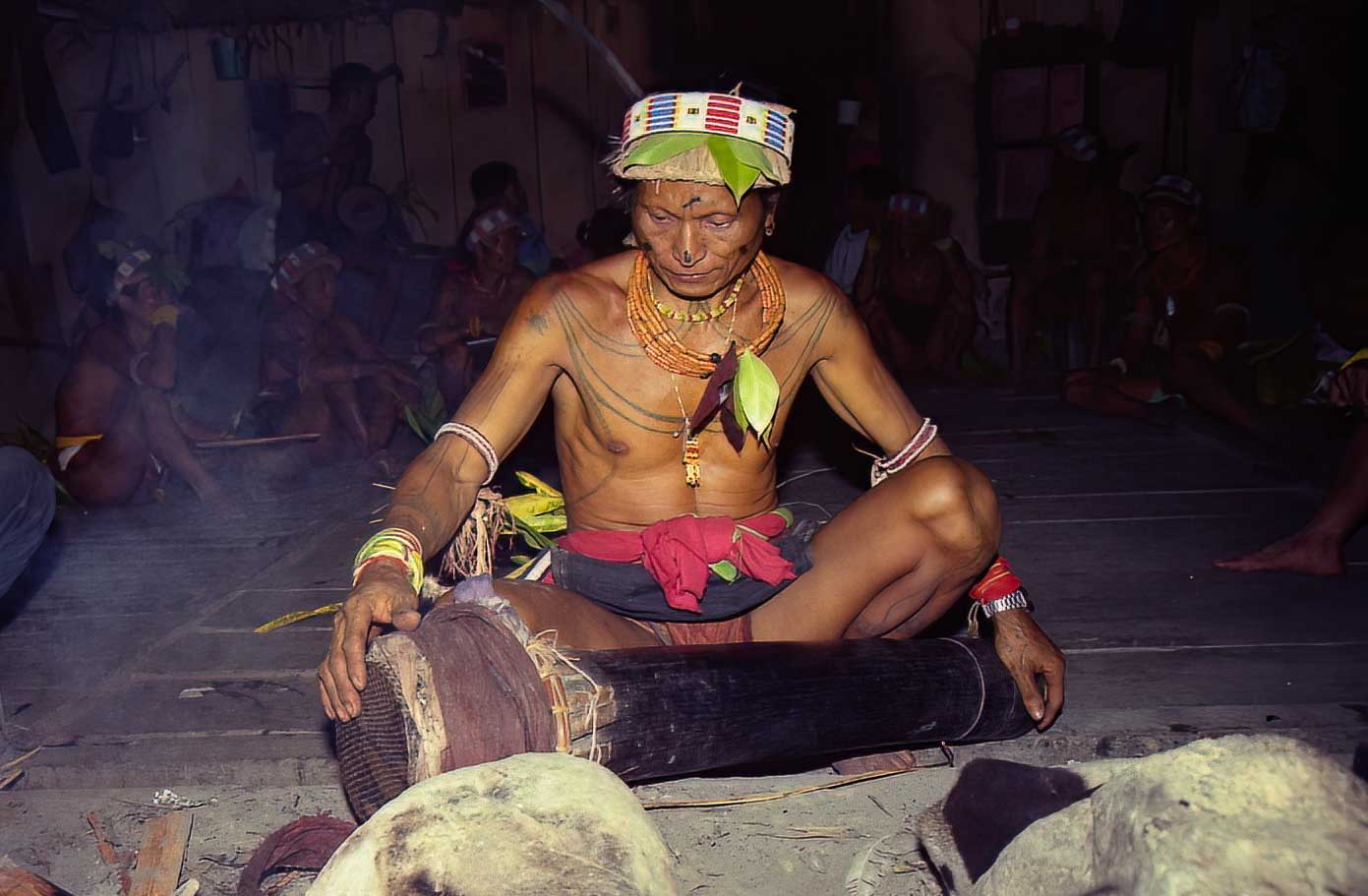

The first ceremony is called Tadde, a festive evening that kick’s off the training. On the evening of Tadde the uma is ritually cleansed and the spirits are summoned. Evil spirits are driven out with a kind of ceremonial whip (nangaingai), made of tree bark and different kinds of leaves. The shamans dance all night long to the rhythms of the traditional drums (kajeuma). The kajeuma is a set of three or four different sized drums, made of palm wood (paddegat) and covered with python skin. Before the drums are played they are heated near the fire, to tighten their python skins. Most Mentawai dances imitate animals, such as birds, butterflies and primates. The night climaxes with trance-inducing dances, when the shamans’ search for spiritual visions, communicating with the world of the beyond. In rare occasions also the wife of a shaman or even other members of the community might go into trance.

After this first communal ceremony the future shaman and his wife have to spend a couple of months in total seclusion, far away deep in the forest in a small dedicated hut (pulaeat). This hut is built by the novice himself, his wife and usually some other family members or friends. The pulaeat is initiated during an intimate private ceremony, with only the novice’s teacher, the paumat, the novice and his closest relatives. During this ceremony the ancestral spirits are informed about the new novice; they receive sacrifices and their help for a successful training is requested.

The initiation ceremony of the pulaeat introduces a period of strict taboos for the novice and his wife, until the final ceremony for the initiation of the novice as a new shaman. Over the next few months the novice and his wife will live a sober life, without any decoration. Their main duty is to raise chickens and pigs and cultivate decorative plants and flowers for the coming ceremonies.

The end of the novice’s period in the pulaeat is accompanied by the third communal ceremony, attended by all members of the uma and anyone else close to the uma‘s community. After this period of confinement and mental preparation of the novice the actual training starts. The paumat teaches the novice all the lyrics and melodies of dozens of shaman songs and chants, and the secret details of rituals which are exclusively known to shamans. Most of the shaman songs are in the ancient language of Simatalu, the place of origin of the Mentawai. This language is only known to shamans.

While the novice is learning, family and close friends make the traditional garb and accessories of the future shaman.

The most outstanding accessories of a shaman are a special head-band, the luat,

and the shaman necklace, the tudda. The luat is made of a strip of rattan, covered with white fabric and decorated with strings of small glass beads. Each clan has its own color pattern. The tudda is a necklace of cylindrical ocher-colored glass beads and usually a few of these necklaces are tied together.

The lekkau is a set of bracelets for the upper-arms, traditionally made of woven red-painted rattan and studded with strings of white glass beads. Over last decade or so the painted rattan is sometimes replaced with strings of red glass beads. The sabo is the dance-skirt of the shamans, made of different colored pieces of cloth and a woven rattan strip at the bottom, decorated with feathers.

The most important and powerful necklace of a shaman is the abak ngalou, made of a strip of woven rattan and decorated with glass beads, with different fetishes hanging underneath. The jarajara is a special decoration for the hair, made of the ribs of sago palm leaves and feathers, with a fetish as well. Shamans also wear a special red loincloth (kabit), made of the bark of a special tree, baiko. The softened bark is colored dark red-brown by soaking it in sap from the bark of a special mangrove tree (toggoro). The entire outfit of the shaman has partly a spiritual and partly decorative meaning. According to the shamans, souls and spirits in the world beyond can only be influenced or communicated with when they meet worthy opponents.

On the second festive night, Sigeugeu, the novice receives spiritual power from the ancestral spirits, while dancing around an elaborately decorated small tree (kinimbu), which is placed next to the uma.

The novice’s training continues, accompanied by regular pig sacrifices.

On the night of Lecu the novice is fitted with a magical anklet of woven rattan, for bodily protection. For the first time they are able to dance in the fire, without getting hurt. The evening is followed by Sigepgep, a night of silence and darkness.

A few months pass. Then is the time for the novice to receive his ‘seeing eyes’. At a secret pool at a hidden location deep in the forest the novice has to swear not to reveal this most intimate secret of the kerei. The novice then gets a splash of a magical potion in his eyes, and he becomes ‘seeing’; from now on he is able to see the souls and spirits of the world beyond. This event is then followed by the culmination of the actual initiation as a kerei: Alup. Huge bamboo poles are erected at the river bank, one for each pig sacrificed during the novice’s learning period. The poles are decorated with sago palm leaves and wood carvings of birds, humans and fish, hanging from the top of the bamboo poles. Similar wood carvings are also hung above the entrance of the uma, to welcome guests, spirits and ancestral and human souls. These wood carvings are called umat simagere, ‘toys of the souls’.

Early in the evening the largest pigs are sacrificed, to commemorate the ancestors. Before the pigs are cooked they are first tied to a large pole and hung above the floor. The shamans then take their youngest children and bless them while running underneath the sacrificed pigs, a ceremony called abimen. A great communal meal follows, with the rimata, paumat, novice and other shamans of the uma and their wives, all in full festive attire. In the evening ceremonial decorations and attire, fabrics and tobacco are laid out on the uma‘s veranda and the ancestral souls are invited to take as much of it as they like. The novice, who now has ‘seeing eyes’, dances around and when the ancestral souls for a split second do not pay attention the new shaman charges forward and grabs a fetish from them. These fetishes are then attached to the shaman’s abak ngalou and a night of traditional dancing starts. Many guests from other umas come to this great event, including other shamans, for whom the other festive nights are taboo.

The shamans dance like birds, fully dressed with their traditional attire with flowers and decorative leaves mimicking feathers. The novice has his body and face dyed yellow with ground turmeric (kiniu). The climax is in the predawn hours, when the lajo-t-abak is danced, the dance of the canoe. The shamans dance anti-clockwise around in a circle, with the rimata holding a small model canoe in his hand, riding the waves and singing about a journey to Pageta Sabbau, a famous mythical kerei with extraordinary powers.

The rimata then sits down in front of the fireplace, personalizing Pageta Sabbau. The novice now dances a part of a bird-dance, but this time without the accompanying rhythm of the drums.

The soul of Pageta Sabbau is invited to come to the uma and give some of his powers to the novice. The novice sits in front of the rimata, who asks the last few questions to test the novice. When the questions are answered correctly the rimata blows in the ears of the novice, to give the novice the power to hear the souls. Suddenly the novice can see the soul of Pageta Sabbau, hovering above the rimata. Powerful fetishes (sineru) hang from Pageta Sabbau‘s head decoration (jarajara). With two hands the novice tries to grab one of the fetishes. He is instantly thrown backwards and crashes to the floor and is overcome with spasmodic fits. His eyes are rolled back, his body sweating and shaking vigorously. Other shamans now jump in and hold tight the novice, to stop the spasmodic fits, while chanting the novice back to consciousness. The shamans then open the hands of the novice, to see whether the novice succeeded to grab a fetish, as a sign of Pageta Sabbau‘s approval of the new kerei. This fetish gives the new shaman some of the powers of Pageta Sabbau and is added to his abak ngalou. If the novice did not succeed to grab a fetish he has to try another time.